There are groups posting this ad for “rape pants”.

They state that because of the staggering number of women being attacked and raped by immigrants, Europeans are advertising these new women’s “rape pants”.

Source: https://t.me/thepeoplesvoice47/8777

This ad is in Spanish, so I assume it wasn't really made for Europe. Nevertheless, it merits more exploration of anti-rape devices.

Anti-Rape Pants

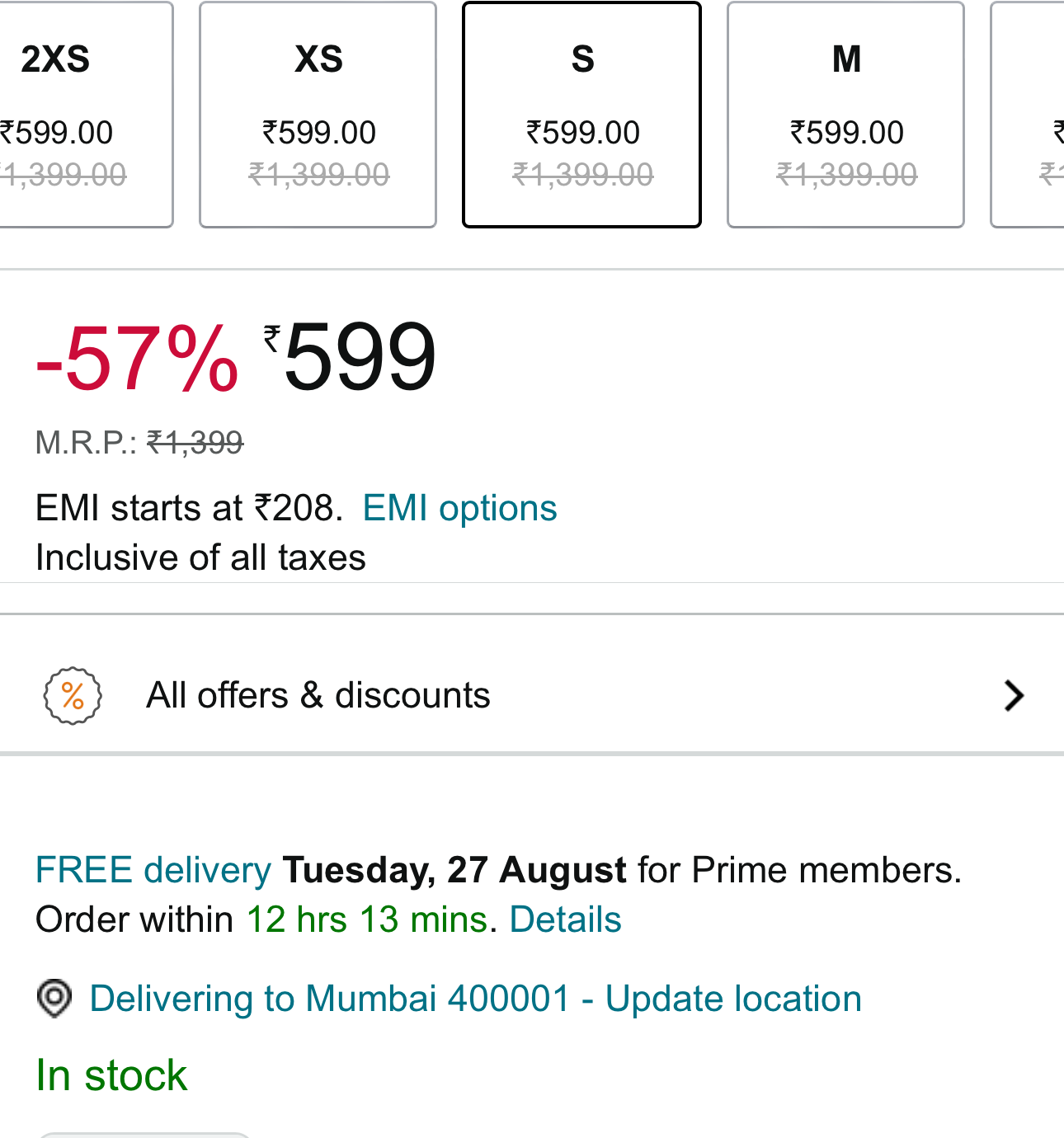

Several different brands carry anti-rape pants.

From India:

Source: https://www.amazon.in/RAYINVENT-Anti-Rape-Mechanism-Girls-Women/dp/B0CH1B4T3M?th=1&psc=1

From Australia

This ad no longer goes to a page:

But did you notice that those pants came with a 130-decibel alarm and are anti-slash and tear-resistant? How do they do that? Are they made of metal?

The History of Anti-Rape Pants

The first ones came out in 2013.

Adding electric shock is an idea, and there are many more.

EKATERINA ROMANOVSKAYA FROZE. It was a warm and sunny day in late May 2000, and the 25-year-old interpreter had just dropped her 3-year-old daughter off at kindergarten in their hometown of Volograd, a city in southwestern Russia, when a man she had never seen before appeared behind her. “We need to talk about the little girl,” the stranger said. Romanovskaya glanced over her shoulder.

She didn’t recognize the man, and there was no obvious reason to run, but Romanovskaya sensed something amiss. Without saying a word, she started walking toward her parents’ apartment, her childhood home. It was a route she could walk blindfolded—perhaps she’d lose the unsettling stranger in the crowd.

When she reached the building, Romanovskaya took the stairs rather than the elevator. It was the kind of tiny decision women make a hundred times every day—instinctive, automatic. But today, decades later, Romanovskaya, now 45, says the decision saved her life.

Because when the same strange man who had so unnerved her on the street broke down the building door and cornered Romanovskaya in the stairs with a hunting knife, she had a chance to scream. “The only thing I had to fight for my life was my voice, so I cried out,” Romanovskaya says. “I called for help as loud as I could.”

Then the man turned the knife on her, and the wall beside her turned red.

“A fountain of blood emerged from my neck,” recalls Romanovskaya. “I reached up to stop the blood with my hands, but my body was totally unprotected. He tried to reach my heart with his knife three times, but my bones saved me: my ribs, my collarbone.” By the time a neighbor came into the stairwell and the attacker fled, Romanovskaya had nine critical stab wounds to her neck, chest, and torso.

Her yoga pants were the only thing that had stopped her internal organs from spilling out onto the floor.

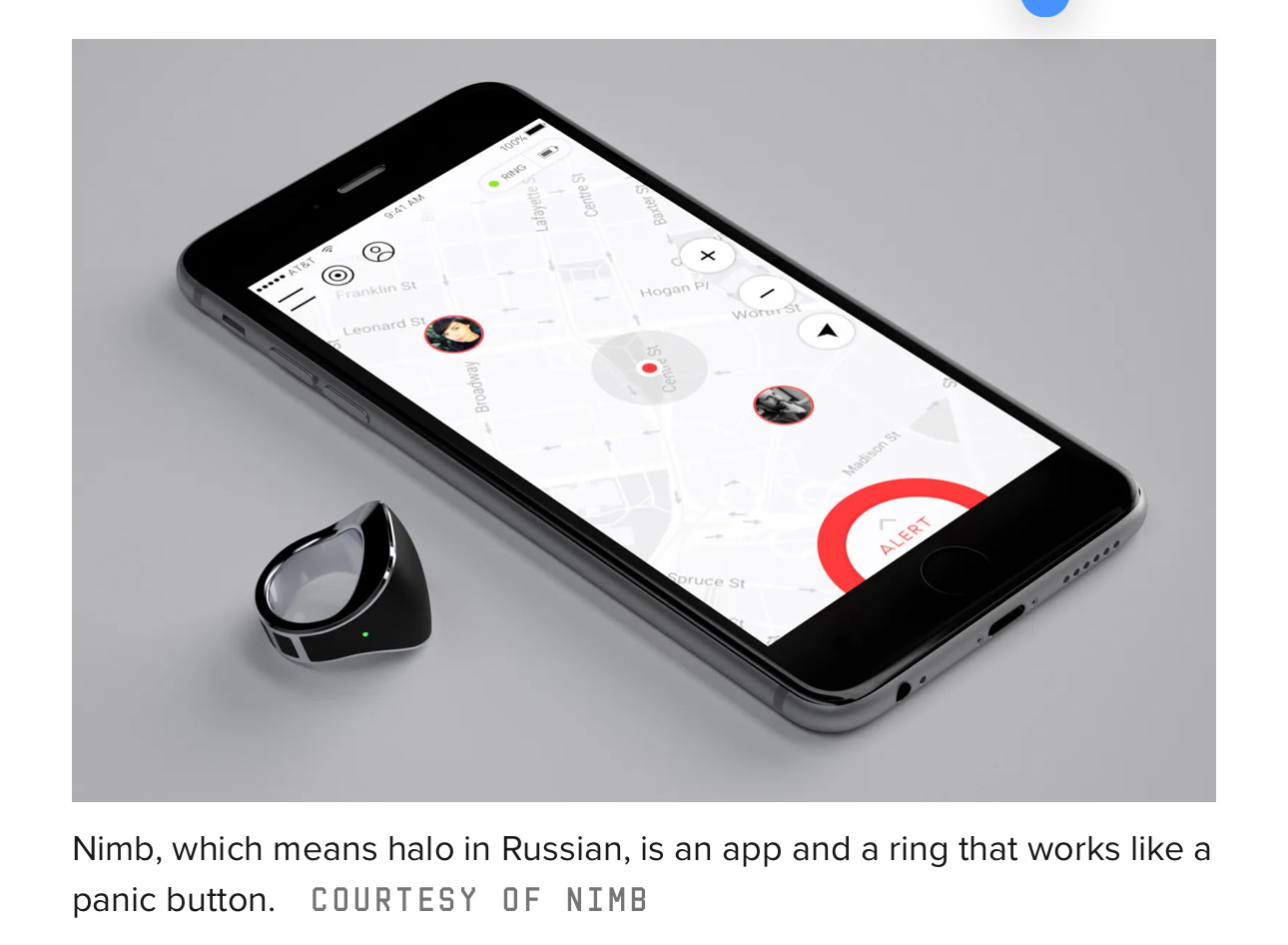

Decades after the attack, in 2016, Romanovskaya, along with cofounders Nikita Marshansky and Leonid Bereshchansky, launched Nimb: a “smart ring” designed to act like a panic button and inform friends, family, and law enforcement if the wearer is in danger.

When the man attacked Romanovskaya in 2000, she had no cellphone to call for help. “I asked myself: What if I’d had a gun?” she says. “But I decided that a gun probably would have made the situation worse. I realized that the most important thing is to call for help.”

Romanovskaya’s invention, she hoped, would help save lives. There was obvious public demand for a device of its kind: On Kickstarter, Nimb (which means “halo” in Russian) quickly raised $160,000 in donations—well over its target goal of $50,000.

But not everyone was supportive. Formal investors balked at the idea—of the “more than 100” investors Romanovskaya estimates she approached, none wanted to get involved. Almost as bad, Romanovskaya says, was the unexpected backlash from the women she was trying to help. It got heated. “They told me, ‘Stop teaching men how to rape,’” Romanovskaya recalls. “But wasn’t it just the opposite? Wasn’t our aim to take the power away from [attackers], and put it back in women’s hands?”

THERE SEEMS TO be a technological solution for everything today, from predicting the weather to finding a date. But can technology solve violence against women, sexual violence? Recent attempts to answer that question have varied wildly, from the sincere to the absurd.

Early this year, an Indian engineer and entrepreneur named Shyam Chaurasia debuted an anti-sexual-violence lipstick gun, which looks like a regular cosmetic but sets off a loud bang and alerts police when activated. In August 2019, an invisible ink stamp meant to mark assailants who grope women on public transport sold out in Japan within an hour of its launch. In China, feminist activists have used blockchain technology to circumvent China’s notoriously censored internet and post information about a decades-old case in which a Peking University student, Gao Yan, committed suicide after she was allegedly sexually assaulted by a professor. And a few years ago in India, three engineers introduced underwear that would deliver up to 82 electric shocks when it detected “unwanted force.”

Some of the inventions seem promising. Others are outlandish, tongue-in-cheek, or even downright medieval. In 2010, Sonnet Ehlers, a former blood transfusion technician in South Africa, rose to international prominence when she announced plans to distribute the Rape-aXe, a barbed “anti-rape condom,” during the World Cup. Her plans went unfulfilled, though, due to a lack of donations. Worn inside a woman’s vagina like a tampon, the Rape-aXe couldn’t prevent rape—but it could punish the offender. In theory, the Rape-aXe’s inward-facing barbs would permit a rapist to penetrate his victim, but then it would clamp down on his penis (without breaking the skin) the moment he’d withdraw.

Once activated, the Rape-aXe could only be removed by a medical professional—giving hospital staff or the victim, Ehlers theorized, an opportunity to notify police. Ehlers says the device was inspired by her experience working with rape victims in South Africa, which has some of the highest rates of sexual violence in the world. Ehlers met women in townships who, they told her, inserted razor blades into sponges that they routinely wore inside their vaginas—just in case. Another survivor of traumatic rape told Ehlers: “If only I’d had teeth down there.”

The Rape-aXe raised comparisons to vagina dentata, the myth of women with toothed vaginas that appears in several different cultures worldwide, including Māori mythology, Shinto legend, and even Hindu theology. But despite the apparent demand for a punitive device like Rape-aXe in South Africa, where an average of 110 rapes are reported to police each day, according to South Africa’s official crime statistics for 2017-2018, the Rape-aXe was widely reviled in international media. Described by South African sexual violence expert Charlene Smith as “vengeful, horrible, and disgusting,” the Rape-aXe provoked a flash of global outrage and then quickly bit the dust.

Some anti-sexual-violence inventions are met with fury; others are met with laughs. In 2007, Japanese fashion designer Aya Tsukioka launched a line of clothing and accessories meant to deceive potential criminals: a handbag that looks like a manhole cover and therefore, if dropped on the street, might trick a mugger into thinking its owner had no purse to steal; a school backpack that unfolds to hide a child behind an apparent fire extinguisher box. But most attention was reserved for Tsukioka’s anti-rape dress: a normal-looking red skirt that could be unfurled to transform a woman into, of all things, a vending machine. A few years later, “revolutionary hairy leg hosiery”—tights that would make a woman look, from the waist down, like King Kong—became a viral sensation on Chinese social media.

IT’S EASY TO dismiss technological solutions to social problems, and many people do. The solution to rape, critics say, cannot be to transform human women into vending machines, Chewbaccas, or mythological monsters.

“Although these inventions are eye-catching, well-intentioned, and draw attention to the fact that sexual attacks and harassment are endemic worldwide,” wrote journalist Homa Khaleeli in a Guardian op-ed. “They only highlight what we have always needed: legislation to protect women that is properly enforced, along with a change in the focus of rape prevention from the victims to the perpetrators.” In an essay for the Independent, writer Layla Haidrani agreed: “We should also be seeing more campaigns that aim to change social attitudes to sexual assault and higher rape conviction rates rather than, you know, crowd-funding gadgets.”

Source: https://www.wired.com/story/to-combat-sexual-assault-women-are-resorting-to-electric-shock-underwear/

It's sad that society needs these things. And that there is a paucity of financial investors. And while I could not find any other anti-rape clothes on Amazon, here are some items particularly good for women and college students.

For Sale on Amazon

Source: https://www.amazon.com/ANKOSHUN-Rechargeable-Personal-Alarm-Women/dp/B0C7CL4VXM/ref=mp_s_a_1_11?crid=344QYPK6SUHBG&dib=eyJ2IjoiMSJ9._tlHKdpzqu3GpvVskQzMJS2_Wdb3oi1Kq4U7OFqlbUW2T2_y44mTrDZsu2BfXQOa3xx0K3y6KGsyeoZw-X0eHP_N9_ua6X2vcxoqLz6WqtS0bWsbs5NpcW7QVKzTnUYEuVRk4Gqh2wV1LjAQ8mbSvIfD0LduzkGt52baY04sYmUVFYaawFW4yadOLBfAvl-MmSLwi78Jyua2wkqlBWy1Mw.MW-jRJelO7XyNXTKx4D2p8M3-XAnUJluxsms2nzzycc&dib_tag=se&keywords=antirape&qid=1724165051&sprefix=antirape%2Caps%2C141&sr=8-11

Source: https://www.amazon.com/Flashlight-Rechargeable-Self-Defense-Anti-Rape-Emergency/dp/B09Q5C9SRY/ref=mp_s_a_1_22?crid=344QYPK6SUHBG&dib=eyJ2IjoiMSJ9.QUMYxpK4E7OzusvLm3h3w7dwzf_vFb1eAwql5egZb1Ytqg5OMOS6-r5g4oeSW4dciBxd9JZjqF9gRggUfh08vKd9b4q0x3otukIlZSuDUAp-WMLQkMTkZCVLye9PLpoU.rD3Uds6VosluPGmTtVybfoBS_nZgi5ogdskX8rNSU3g&dib_tag=se&keywords=antirape&qid=1724165083&sprefix=antirape%2Caps%2C141&sr=8-22

The best way to find these items is to search “personal protection”.

At the rate the raping is going on it won't be long before the "men" of today will need them.... think of all the poor trans 😬

Seems odd that the woman who was almost killed in an attempted rape would say that a gun would only have made things worse.