The Pathophysiology of Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome:

Why Patients Faint

Most people don’t have to think about what happens when they stand up. Those with Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (PoTS or POTS) need to do so or they may faint. POTS is a dysautonomia, so some use the terms interchangeably. It is a heart and blood vessel complication suffered by many after a virus infection, including Long COVID.

Depicted in old films having a young woman who lives in a day bed and constantly faints into the arms of her knight, it is likely synonymous with "The Soldier's Heart", coined by Sir James Mackenzie in 1916 (Kavi, 2012). It was not until 1993 when the syndrome was defined as PoTS (Raj, 2020).

The brain needs to get blood in order for it to get its own oxygen supply. If something happens to compromise the blood supply to the brain (and thus the oxygen supply), the body automatically compensates for it. God-given compensation mechanisms are triggered, and the body tries harder and harder to prevent the brain from losing blood supply and oxygen. This is the basis of POTS: the math of the brain.

The Pathophysiology of Standing

When one stands, 500 ml blood descends from the chest cavity or thorax. Normally, the “automatic” or autonomic nervous system immediately adapts. Blood vessels in the legs tighten and narrow, squeezing blood back up to the thorax. However, in those with POTS, the mechanism fails. The legs pool with blood.

In an effort to compensate and keep blood going to the brain, the heart rate beats more often. While the definition of POTS is an increased heart rate greater than 30 beats per minute, it is not set in stone. Catecholamines or epinephrines also levels 2 also increase but this is not easily detected in the blood or urine. Brain blood flow diminishes, usually in the absence of a low blood pressure, or hypotension 3, although this also is not a requirement.

God-given compensation mechanisms are innately triggered when low blood flow in the brain occurs. If not met with enough compensation, the brain can not function. As it fades out, the final compensation is to experience a “gray-outs” (i.e., pre-syncope) where one sees gray and has an impending sense of doom. If low blood flow continues, the ultimate compensation is to lay the body flat so the brain can finally get enough blood. Finally, the patient faints, also known as syncope.

The compensation for low brain blood flow is such that the body tries harder and harder to get more blood flow, and therefore oxygen, to the brain. The body doesn’t want to faint.

The basis of understanding POTS is to know the math of the brain. To understand POTS, one must first understand both the nervous and the circulatory systems. The Nervous System This is comprised of 1) the central nervous system: brain and spinal cord, and 2) the peripheral nervous system: all the nerves from the spinal cord going to and from the muscles and visceral organs, like the stomach. We can think of the nervous system as such that everything in the nervous system is "automatic". Nothing controlled by the autonomic nervous system happens with the deliberate mind. It encompasses such things as blood pressure, heart rate, food digestion, the motility of the stomach and intestines, the production and elimination of urine and feces, sexual function, sweating and goosebumps. Dysautonomia/POTS Dysautonomia is "dysfunction" of this "automatic" or "autonomic" nervous system. Upon standing, the dysregulation prevents calf veins from constricting and tightening up to squeeze blood back up to the thorax. As brain blood flow decreases, it sends out "autonomic" or "automatic" signals crying for help to save itself. It tries to pump more blood to itself. Upon failing, the person faints. The Circulatory System With POTS, the pooling of blood in the legs and may cause fluid leakage out of blood vessels, leading to discolored or swollen lower legs. When the blood pools in the legs, it decreases the amount of blood returning to the heart. In turn, this means that the heart is "less filled" with blood, so it pumps significantly less blood forward to the brain and other vital organs. The Math of the Brain If you are mathematically inclined or want to learn some math of the brain's blood supply, read on. If not, you may skip this section. But I hope to explain this in a short and common-sense manner that is easy to understand. You may have to pause or read it twice, but I promise it will be worth it. When triggered by a threat, the only way that the brain receives more blood is by a built-in mathematical equation that operates as a reflex, or automatically. The equation has to do with cardiac (heart) output (CO).

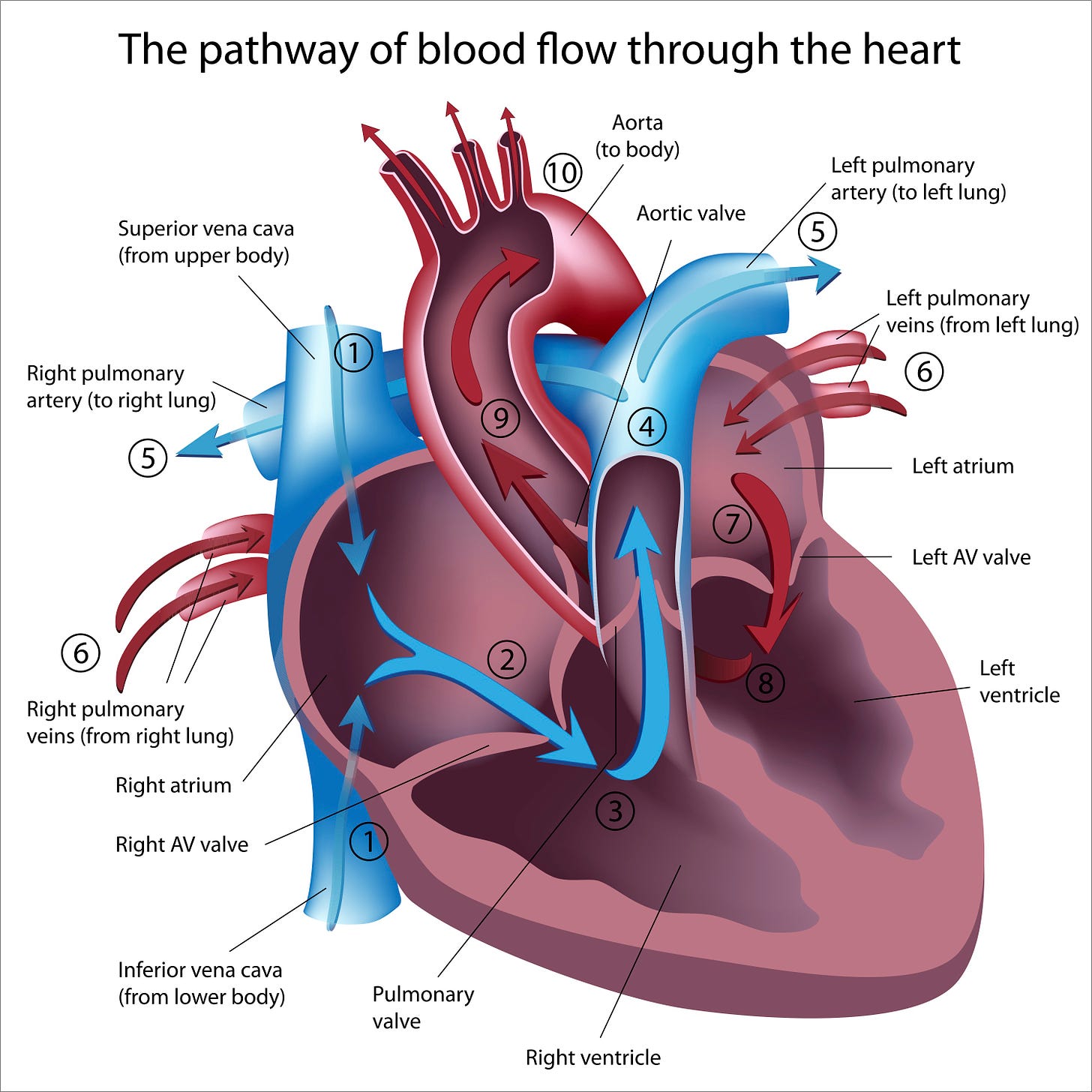

To pump blood to the body, the heart has to fill and it has to beat.

Cardiac Output With each beat, a volume of blood is delivered to the rest of the body. This volume is termed cardiac output and there is a mathematical calculation that determines this blood flow. The formula for this is: CO = Heart Rate (beats per minute) x Stroke Volume (ml) CO = HR x SV A normal adult cardiac output is 5 liters per minute. A normal heart rate is 60-100 bpm. Cardiac output is the amount of volume the heart pumps out through the aorta, the largest artery in the body that comes straight out of the left ventricle (see #10 in image above). Cardiac output depends on two things: the heart rate and the volume of blood that is pumped out per heart beat. The heart can't pump blood out unless it received blood into it (see #1 above, as blood goes into the left atrium via the superior and inferior vena cavae) to maintain circulation. Therefore, it makes sense that the stroke volume depends on venous return or the amount of blood going into the heart for recirculation. In a perfect heart, venous return equals cardiac output: exactly what goes in, comes out. The force of contraction is another factor determining stroke volume. If the heart contracts to squeeze blood out with a lot of force, stroke volume and cardiac output increase. If a person has heart failure or a "weak heart", it does not eject enough blood with each beat. If you are dehydrated or lost blood, you have less blood volume or stroke volume, in ml/minute. The body compensates for this by increasing heart rate. If your heart rate is too slow, it is providing less volume per minute, so the body compensates by increasing stroke volume. Failures in both mechanisms lead to syncope or fainting. To keep blood going to the brain, one factor compensates for another in a positive feedback loop. If your heart rate is too low, the stroke volume has to increase so the brain gets enough blood. If your stroke volume is too low, the heart rate has to increase to maintain cardiac output. With POTS, leg pooling of blood means the volume is low, so less is delivered to the heart, less goes out, the brain cries for help, and the heart rate goes up. During loss of blood, dehydration, and POTS, blood volume is low and the heart may compensate by increasing its heart rate. Hence, the orthostatic hypotension, i.e., low blood pressure, automatically causes the heart rate to go faster, i.e., cause tachycardia. This is the defect in dysautonomia: lack of blood returning to the heart (#1 in image above), partly because it's pooling in the legs and partly because the blood volume is not large enough to return enough blood to the heart. Hence, the acronym "POTS" is named: P = Postural: upon standing or changes in position, the patient experiences symptoms O = Orthostatic: low blood pressure occurs because the legs pool with blood T = Tachycardia: to compensate for decreased stroke volume, the heart rate increases S = Syndrome: this happens over and over again, usually in a predictable manner. If you would like more information that reinforces the physiology of the heart, a good website is HERE. Triggers of POTS POTS can be aggravated by position changes such as standing, not eating enough salt, not drinking enough fluids, prolonged standing or sitting, alcohol consumption, blood-pressure lowering medications, sweating too much, heavy meals, or being in a hot environment. Forms of POTS Neuropathic POTS: Peripheral denervation (loss of nerve function) causes poor blood vessels in the muscles, especially in the legs and core body. Hyperadrenergic POTS: Overactivity of the sympathetic nervous system. The different types of POTS may overlap and patients do not have to fit a specific type. Each case of POTS is unique. Symptoms may come and go over a period of years. In most cases, symptoms are alleviated with compression stockings, increased fluids and salt, diet, medications and altered physical activity. Stay tuned for more on symptoms in our next newsletter. The best news is that symptoms may completely subside with treatment, and if an underlying cause is found and treated. Be sure to see our future newsletters for more on POTS: symptoms, diagnosis, co-morbidities, and treatment. Many doctors don't know what POTS is and you can help someone get their diagnosis, leading them to get the right treatment. I lived with POTS for twelve years in bed, so if you know someone who is bedridden, especially after having COVID, please help them get a diagnosis. Many patients are told this syndrome is "all in your head" or is just "anxiety" or a "panic attack". Anyone with POTS is anxious and feels normal "panic" without enough blood supply to the brain! This is NORMAL... and it's NOT all in your head - it's in your LEGS too! Thank you for being you! With your help, we can help Long Haulers get a diagnosis so they can get the right treatment. If you know someone with POTS or possible POTS, be sure to forward this link to them. You can also be a big help to general population of those with Long COVID by sharing this article on Facebook, Twitter, or Instagram. We're big on Twitter, @TheRebelPatient. Feel free to tag us in your Tweets by just using @TheRebelPatient. References

Aranda, M. Guidebook to Low Back Pain: Diagnosis and Treatment. Self-published, February 26, 2021.

Kavi L. Consider postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome in patients with syncope. Am Fam Physician. 2012 Sep 1;86(5):392, 394. PMID: 22963054.

Mar PL, Raj SR. Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome: Mechanisms and New Therapies. Annu Rev Med. 2020 Jan 27;71:235-248. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-041818-011630. Epub 2019 Aug 14. PMID: 31412221.

Raj SR, Arnold AC, Barboi A, Claydon VE, Limberg JK, Lucci VM, Numan M, Peltier A, Snapper H, Vernino S; American Autonomic Society. Long-COVID postural tachycardia syndrome: an American Autonomic Society statement. Clin Auton Res. 2021 Jun;31(3):365-368. doi: 10.1007/s10286-021-00798-2. Epub 2021 Mar 19. PMID: 33740207; PMCID: PMC7976723.

Amazing and sad 2024 and some docs still don’t acknowledge. Just no cash in it after all.