What it Was Like to Help Someone in the Process of Dying

Giving Morphine to Provide Comfort, Not to Hasten Death

I went into the next room to see my next patient.

Saving A Life

As I entered the room, my patient passed out right in front of me quite suddenly. One moment, she was standing up next to me, and the next moment, she was on her back, on the floor, and without a pulse. I saw her head hit the floor, and checked to confirm there was no bleeding under it.

I didn't know exactly what to do, and there was nobody there but me. I was just an intern, and had literally just graduated medical school two months prior. I had been accepted for internship at very large metropolitan teaching hospital at the University of Southern California (USC) Medical School. I would be there for both internship and a portion of my residency in anesthesiology. It was a huge hospital with a ton of staff, but I was the only doctor on the ward.

Because I had already been at USC med school, my hands-on experience was quite heavy. I already delivered a hundred babies practically on my own, done spinal taps without supervision, and drawn blood on patients in the Jail Ward in the dark to avoid waking up the whole room.

Now I descended to the floor and verified that my patient was not breathing. So I commenced CPR. I gave breaths - did compressions - CALLED A CODE AND YELLED FOR HELP! - gave more breaths - did more compressions - until help arrived. I did it exactly as taught for my CPR certification.

Image Source: SwissCows.com

And then…

… She coughed! She started breathing!

By then, the CRASH CART from down the hallway was still being wheeled into the room, not yet unlocked or opened.

Image Source: SwissCows.com

We never opened it.

I put on some oxygen, got ready to put in an IV, and realized that this was the first life I saved. By then, the room was filled with anxious interns, residents, and Fellows. As she wheeled out to get ready for emergency surgery, she thanked me for saving her life. The enormity of what just happened began to weigh on me.

It ended up that she had a blood clot to her lungs that was surgically repaired. Had I not been there at that moment, no one would have known that she had stopped breathing and was dying on the floor.

What a feeling: to save a life!

Not every life was ours to save.

Some were already dying, and there was nothing we could do to stop this process.

NOTE: This next section walks through a patient who was dying and in whom I gave IV morphine to help with “air hunger”, until the point where he passed away. It may be disturbing to some, especially those who have lost a child to the hospital killing protocols. I want to emphasize that I did not give morphine to kill the patient, who was already in the process of dying. I gave it to make him comfortable. There's a way to do it.

Comfort Care

I went into the next room to see my next patient.

He was already in the process of leaving this world, and it was obvious. He struggled to breathe, making raspy noises. Actually, I felt quite awful upon seeing him, due to his obvious discomfort. Every fiber in my body wanted to help him. If you could hear him, I am sure that your reaction would be the same.

It was inhumane, how he suffered.

In my mind’s eye, even though I knew that I was alone, I turned slightly to my right and to my left, hoping that a nurse or anyone had followed me into the room. Alas, no.

I was alone.

Because my Attending told me that I would be here for an hour, I immediately pulled up a chair as close as I could, so that I could hold his hand and have IV access. I had been told that the pharmacist would bring me syringes of morphine and that I was going to simply make him comfortable, and then keep him comfortable.

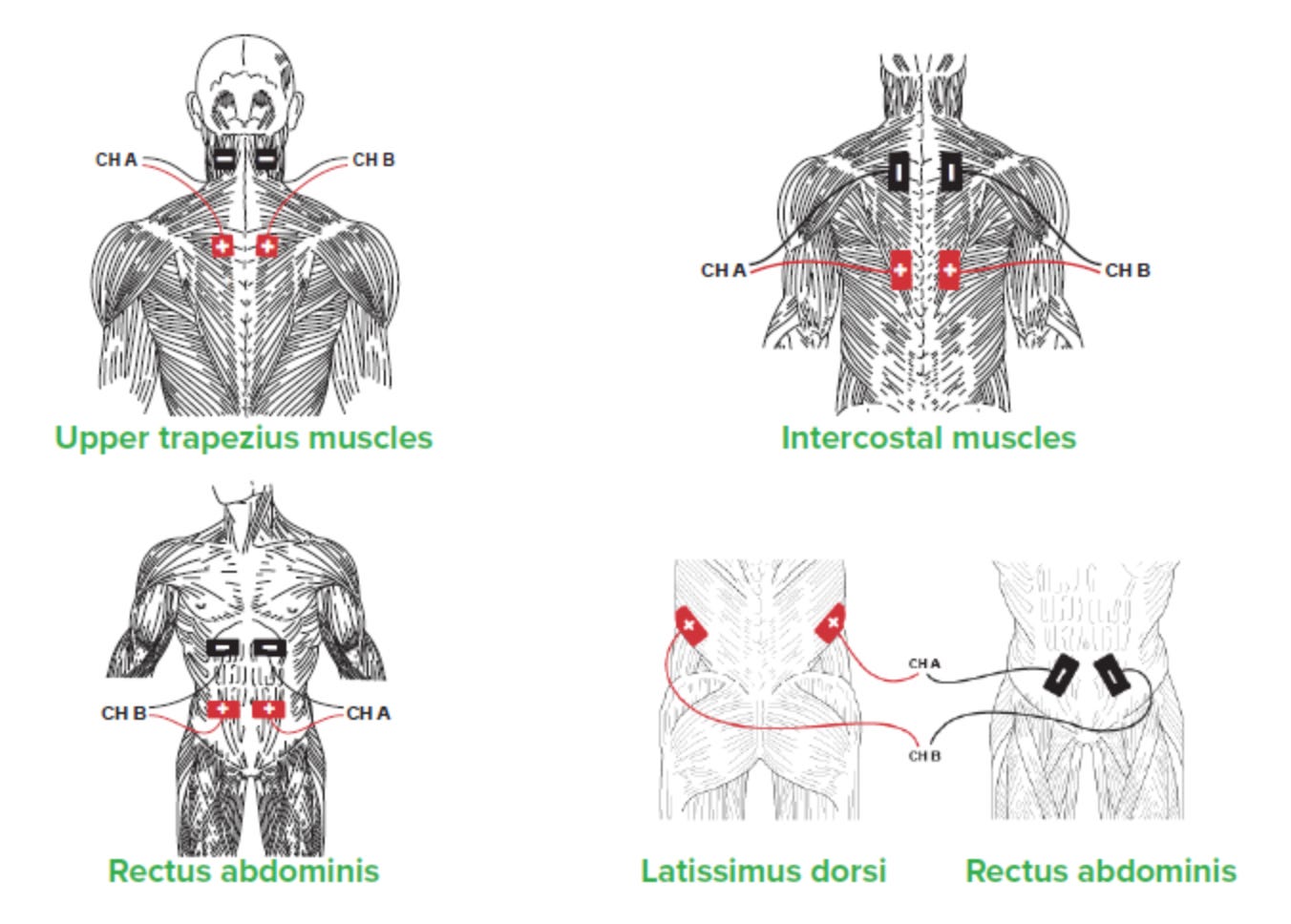

As a doctor, I noted that he used his “accessory muscles of breathing”. His nostrils flared. His neck was tight, and you could see every muscle: the scalenes, the upper traps, the rectus abdominus, the lats, the subclavius, the sternals, the cleidos, and the mastoids, the sternocleidomastoids, the SCMs, and the intercostals, the tiny muscles lining each rib. They sucked in and sucked out and his breaths were stacking so high that his chin was elevated as if he was dangling by the pool with his chin on the deck.

Accessory Muscles of Breathing

Image Source: Swisscows.com

I hated it.

A LOT of energy was being expended JUST TO BREATHE.

Because the patient and the family did not want ‘extraordinary’ measures, he had already been wheeled out of the ICU and was now on the regular floor. My Attending told me to stay with him and watch two things: his pupil size and breathing rate. He said to use these to give him morphine “whenever he needed it”. That’s all that I needed, because I knew what it meant.

It wasn’t hard. Morphine helped him breathe better; it stopped those ugly, raspy noises. Breathing too fast/raspy? Give a bit more morphine. Pupils dilated wide open? Give a bit more morphine. Just don’t give too much, or I would cause him to altogether stop breathing, which would be the same as killing him. I stayed far away from that.

I was glad that I had morphine in my hand, or it would have been extremely inhumane to watch, to hear, or to witness his slow, torturous, eventual departure from the world.

Holding Hands

The best anesthesia is holding hands.

And yes, I held his hand as much as possible, and that offered sentimental comfort for us both, a dose of humanness that could not be underestimated. I could sense his panic through hand-holding, and feel his sweat. His fight-or-flight reflex was in full survival mode, eyes dilated.

The power of human touch, of holding one’s hand during death, was a moment when time was suspended. As soon as he grasped my hand, it was like the heavens opened. He was SO GRATFUL that I could almost feel the light of God descending upon both of us, as if there was no one else in the entire world but us two.

Source: SwissCows.com

At first, he clutched my hand in panic, with the same intensity as a drowning person clutches a lifeguard. It was as if he wanted to climb out of the drowning and submerge me together with him because the drowning was so imminent, and he just didn’t want to go it alone. And like the lifeguard that I used to be, I recognized that he could take both of us under the water, so I knew in my spirit that he was dying and about to go any minute.

I knew it.

I have since said many prayers, held many hands. My prayers were both whispered and said aloud, hoping for relief and offering passage into the next world.

We prayed. I closed my eyes,

“Father God, help this man pass into Your hands. Help me help him in the perfect ways. In Jesus’ Name. Amen.”

Holding hands could not take away the feeling of impending death, nor could anything else. After we prayed, I knew that I was made for a time such as this, and that I could do this the right way.

The Last Moments

In the beginning, he breathed fastly as he struggled, over 40 times a minute. As I gave morphine, he was more comfortable, as everyone in Palliative and Hospice Care knows that it is the ONLY drug that helps alleviate “air hunger”.

I gave a bit of morphine in the IV. And his breathing was more comfortable, down to 36 breaths/minute. His pupil size was the same. When I saw it was wearing off, I gave more morphine. After about 30 minutes, he attained a normal breathing rate of 8-12 times/minute. He stopped still struggling to get more oxygen. He could not talk, but I asked him if he was much better now, and he nodded his head, “Yes” as he placed his palm over his heart.

This went on and on, as I titrated morphine to his breathing rate while checking the pupils to be sure I wasn’t overdosing him. In this fine balance, a bit too much morphine would make him stop breathing and kill him; but a bit less than that and his adrenal glands and fight for oxygen would keep him struggling to breathe.

I walked this rope with him.

Eventually, he was comfortable. His breathing rate was close to normal, now eight times per minute. There were no noises. There was no struggling. He was ‘floating’ on the morphine, and it was holding his comfort in check.

And then, he lost his energy. All that fast breathing had taken its toll. And the relief from the morphine had relaxed his body so that it could succumb to the process of dying. Six breaths per minute went to two. He was still comfortable, breathing slowly and without strain.

And then he took a big breath, and it was his last.

I didn’t move.

My eyes were already on my wristwatch so I noted the exact time of death.

I kept holding his hand, even as its temperature turned from warm to cool. I kept talking to him, even though I wasn’t sure if he could hear me. And I kept praying because that is the only thing that I really knew how to do.

Only after more than three minutes passed did I lift my head from our clutched hands. I dried my eyes and prayed again for his soul to meet God in that wonderful place with No More Tears, that place that I later visited (see HERE), that great place where we all want to go, that beautiful place that doesn’t ever see one tear. That is the place that is so happy that I don’t want anyone to cry for me - because if they knew my joy, they would have a PARTY!

Putting my humanity aside to task myself with proper channels, I ensured there was no heart rate, no EKG, no breathing.

And I declared him dead.

The nurses took care of everything else from there, as I left to go underground in the basement to the morgue. I filled out the Death Certificate, noted the time of death and the causes of death, and then signed my name.

Right then, my beeper went off. It called me back up to the ICU, so I headed back to the elevator. As I arrived to the floor, I took a deep breath and straightened my hair.

And then I went into the next room to see my next patient.

See Also:

My most popular post:

And…

On Dying and Going to Heaven:

Dr. Arande, that was beautiful. Thank you.

God bless you Margaret. You are one of God's angels.